Resistance of Vegetable Species to Disease and Pests

How is resistance evaluated for registration in the Catalogue?

Towards the end of the 1950s, public and private research began creating genetic material which was resistant to diseases and insects. This research, which was initiated in America, intensified in Europe and Asia, and was recognised as a priority in Europe. Starting with resistance to phytopathogenic fungi, research then went on to explore viruses, bacteria and insects.

There are now almost 150 host pathogen and pest combinations across forty cultivated species, which are used for breeding programmes based on identified resistance genes. A breeding academy for disease resistance has also been created in Europe in response to some of the sanitary problems that are developing at this time of major agroecological intensification.

Monogenic resistance

For many years, breeding programmes were oriented towards high-level monogenic resistance in an effort to solve major phytosanitary problems.

Polygenic resistance

Failing to obtain high-level monogenic resistance which was sufficiently durable, research was oriented towards quantitative and partial polygenic resistances, called intermediate resistances, the aim being to associate resistance with other production factors to prevent rapid resistance breakdown.

Insect resistance

Plant breeding for insect resistance has proven difficult due to the absence of genetic symptoms of simple resistance. Nevertheless, aphid resistance genes have been bred for melons (Vat Aphis gosypii resistance gene) and lettuce (Nasonovia resistance). Despite some resistance breakdown being observed, these two resistances have shown to be high-level and sufficiently durable.

Programmes are underway for other vegetable species insects, with research focusing on diversified combat mechanisms (leaf structure, hairs, exudates, etc.).

This area of research and plant breeding for genetic disease and insect resistance has therefore been a major success, and has become an essential tool across the world.

Resistance testing for registration in the Catalogue

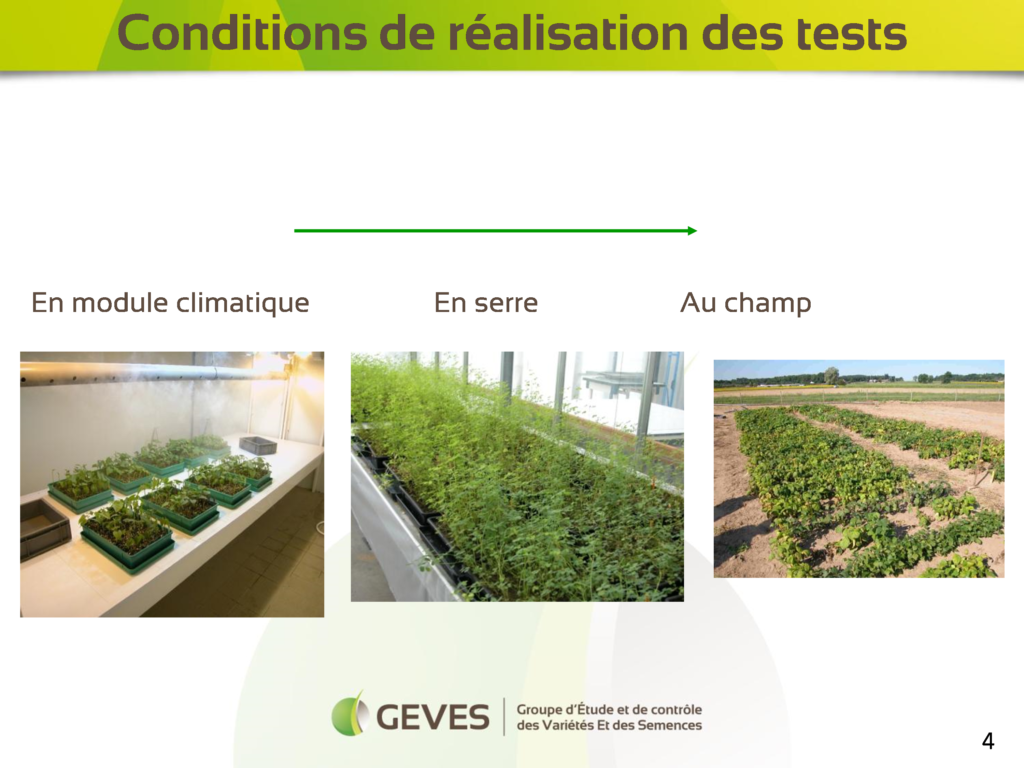

GEVES is responsible for characterising varietal genetic resistance on behalf of the CTPS, in the framework of variety registration in the French Catalogue. This concerns almost 100 host/race/pathogen or pest combinations and thousands of official tests, used to to evaluate the reference collection and new varieties. This evaluation consists primarily of bio tests, conducted in a confined space (greenhouse or climatic chamber) on young plants with a response time after rapid inoculation (2-4 weeks). Some pathogen resistances are tested in-field with enhanced contamination conditions.

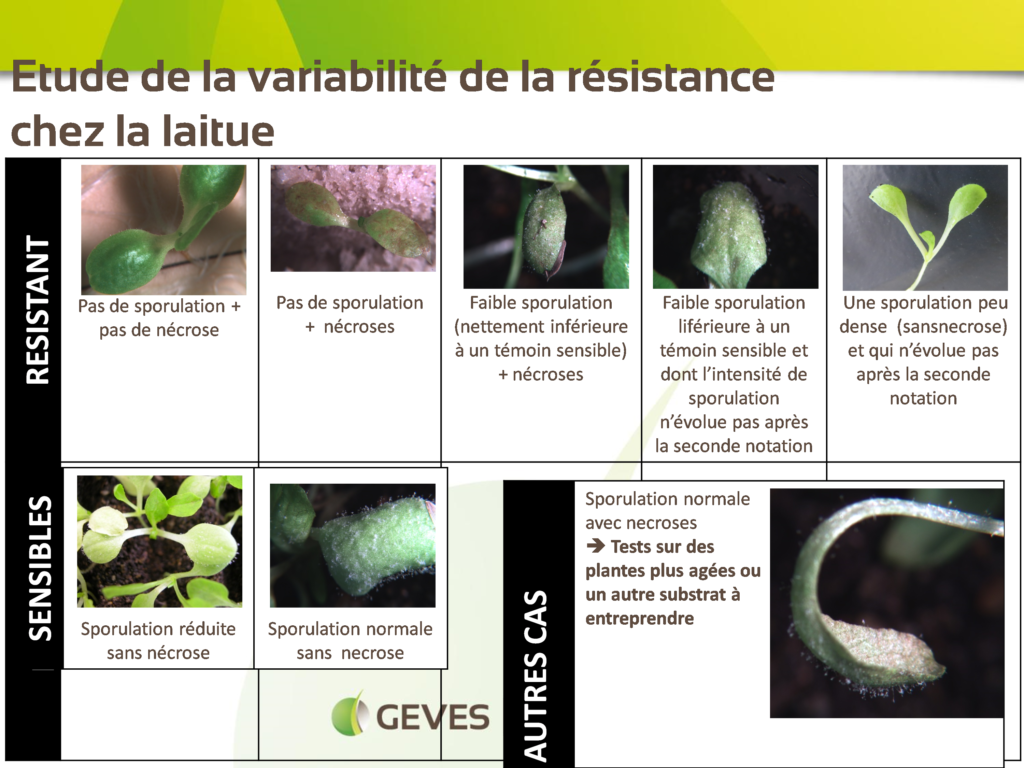

These tests evaluate a variety’s behaviour in relation to resistant and sensitive comparison varieties. This involves characterising a plant’s expression of resistance, its phenotype. GEVES follows protocols for evaluating resistance which are approved or recommended by the CPVO, UPOV, INRAE and the CTPS. They must be reliable, reproducible, and representative of the resistance in natural conditions.

Testing methodology is based on:

- Validated reference varieties (sensitive, resistant, intermediate resistance) with seeds available

- Validated and available differential hosts (comparison varieties)

- Strains or isolates of reference pathogens or insects which are validated, available, durable, and representative of field reality. GEVES maintains a collection of 250 reference strains.

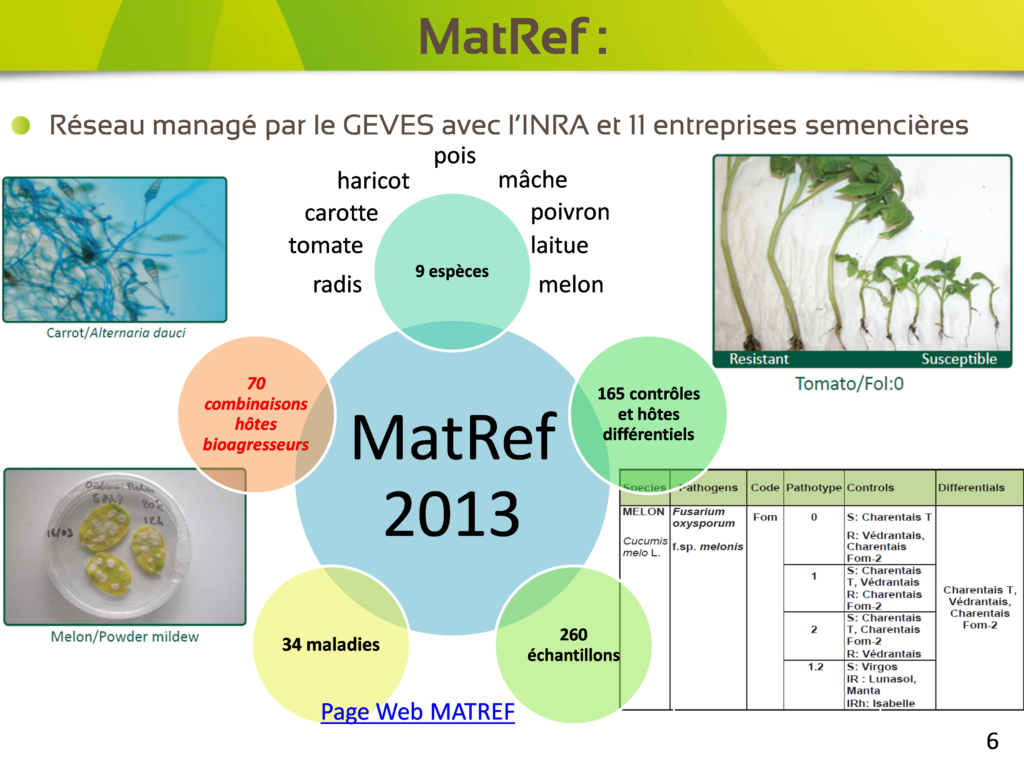

Each year, GEVES characterizes the genetic resistance of new varieties to breeds or strains of pathogens and pests: cucumber (7), spinach (3), bean (5), lettuce (20), lamb’s lettuce (2), melon (12), pepper (10), pea (5), tomato (19).

In collaboration with its research partners, GEVES has created a network for maintaining and distributing these varieties and strains called the MATREF network. This network aims to make reference material openly available.

- List and prices

- Contact: matref@geves.fr

Methodology development projects are regularly carried out at GEVES in order to:

- Standardize methods with other Examination Offices and breeders in order to optimize the consistency of results and define reference material

- Develop and improve methods for evaluating variety resistance to pathogens and pests

- Validate these methods to obtain reliable and recognized protocols at international level

- Study new pathosystems and develop methods for measuring genetic progress in genetic resistance of pathogens and pests for cultivated vegetable species. This is a priority component of the “Plan Agro écologie 2016”.